Publicado originalmente en Medium – Manuchis

I have released a series of articles regarding Empathy (here, here and here), its importance, and the misreadings that led to its disenchantment. It is time to turn the page and to address it from a creative perspective. How do we create scenarios and experiments with empathy? How do we develop better interactions? Alternatively, how do we design better spaces? During my research, I’ve tested, refined and experimented with different methodologies, perspectives and ontologies.

‘So here is the question I wish to raise to designers: where are the visualisation tools that allow the contradictory and controversial nature of matters of concern to be represented?’ (Latour 2008, 13).

In this article, I will dirt my hands with that question by selecting and classifying tools for thinking-doing, and to approach processes of invention. It can be dangerous to assume that this classification is closed, exhaustive or, moreover, sufficient to any project. On the contrary, I’m trying to summarise, and help designers to speculate more to open possibilities.

Instead of delivering ethnographic-informed design, we account on the importance of the procedural form of creation. The difference is on the constant inquiry on subjectivities and our attunement of ‘what bodies do’ in the process of design research.

‘We need to shift from thinking about methods as processes of gathering data toward methods as a becoming entangled in relations’ (Springgay and Truman 2018a, 2).

‘The focus is on how things come together, how they need and reinforce one another’. Paraphrasing Latour, ‘it is not sufficient to address concerns about co-habitation or the possibility to disagree’ (Storni 2016, 170).

‘Being careful in drawing things together and making things public requires the agnostic designer to move slowly and cautiously. The potential danger in this instance is of antagonism between the actors who, when drawn together and given a visible public voice, might see themselves as enemies rather than legitimate adversaries designing things together’ (Storni 2016, 176).

I like the idea of invention, that ‘involves an active search for alternative ways of combining the representation of, and intervention in, social life’. Following that statement, social life should not be understood as given, but ‘performed, materially conditioned or constrained, and/or reflexive, i.e. it is transformable through knowledge, intervention and creativity’ (Marres, Guggenheim, and Wilkie 2018, 37:18). Thus, social life, cannot be engineered.

Classification of methods

I conceive this compendium of methods and strategies in what could be inscribed into what Vannini calls non-representational methodologies. However, choses one or another method or strategy ‘are all but random, as large bodies of knowledge — both practical applications of methods and strategy, as well as more abstract reflections on pros and cons and on epistemological foundations — have accumulated over time.’ (Vannini 2015, 11). Moreover, ‘the unquantifiable within experience can be taken into account only if we begin with a mode of inquiry that refutes initial categorisation. […] When something does, new relational fields are forming, and with them, new modes of existence. A new mode of existence brings with it modalities of knowledge.’ (Erin Manning in Vannini 2015, 54) .

‘Methods can be practices of generating research and methods for dispersing the research with different publics simultaneously’ (Springgay and Truman 2018a, 9).

In any case, ‘inventive social research assumes the performativity of its methods in the curation of its objects of study’ (Marres, Guggenheim, and Wilkie 2018, 37:26). Consequently, these are not fixed steps to be followed, like in Human-Centered Design or Design Thinking approaches. These methods are classified in three categories: create, collect and analyse. The purpose is to provide specific outputs, but all could happen at the same time, and it is at the researcher body/mind to account it, to make it a better process. Even more, all of them are reusable and can be mixed and modified to change its nature. In the end, what it counts is to provoke a break in our subjectivity, to re-think, re-enact and attune to what is happening.

Create

To create new things is to play with materialities, affordances, and assemblages. In other words, is being open to the relations between things. Because we focus much on what happen in-between relations, it is good to explore the process of creation as a process of thinking. These tools provide a different way to attune to, look through and becoming part of what we may create.

Research-creation

Research-creation is a form that denies method, a practice of knowing by doing. In order to Erin Manning, ‘methods safeguard against the ineffable’ or the (in)tensions (Springgay and Truman 2018a; Vannini 2015). She looks for a way to develop a radical empiricism that remains critique, without imposing a concrete method. What else can be created, sympathetically, in the encounter? What can be done previous to the modes of existence?

‘Making and thinking, art and philosophy, will never resolve their differences, telling us in advance how to com- pose across their incipient deviations. Each step will be a renewal of how this event, this time, this problem, proposes this mode of inquiry, in this voice, in these materials, this way’ (Vannini 2015, 69).

To be clear, research-creation can be useful when we want to start from the pure experience, without expecting anything. Maybe one of the more abstracts forms, in rational terms. However, many explorations could lead to new insights, new relations ad well as (in)tensions.

Things doing

But, what about the thing that we try to design? Or, howother things ‘do’ in the same space that we are looking for new ideas? McCormack explored the idea of attending to the properties and qualities of things. His interest was in ‘turning things around: defamiliarizing them; placing them in generative juxtapositionings that allow thinking to grasp a sense of liveliness of the worlds of things anew, however modestly’ (Vannini 2015, 93).

With its origins in queer scholars and ‘alien phenomenology’, defamiliarization is a common strategy in researchers who want to explore how things are doing outside their own interpretation. As an example, the author used a balloon, where its form of existence creates, extend and relates with other bodies. By becoming things, is to attend to the emergent, discrete and unfinished trajectories, materialities, affects, perturbations, atmospheres, intentions, complications and controversies that are in relation.

Things doing is a form to connect to other modes of existing, to explore new possibilities of becoming, rather than assume such relations to the world from the individual perception.

Enlivening representations

Vannini (2015)defines it as ‘a series of rhetorical options, strategies, and practices directed at making ethnographic representation less concerned with faithfully and detachedly reporting facts, experiences, actions, and situations and more interested instead in making them come to life, in allowing them to take on new and unpredictable meanings, in violating expectations, in rendering them (on paper and other media) through a spirited verve and an élan that reverberates differently among each different reader, listener, viewer, and spectator’ (2015, 119).

The task here is to take questions, or perspectives, or critiques, or forms of ‘if’ (exploring questions as what if, as if, even if…), he calls it ‘irrealis moods’:

- The dubitative mood expresses doubt and uncertainty.

- The presumptive mood similarly connotes doubt, but also curiosity, concern, ignorance, and wonder.

- The hypothetical mood is an explorative tone that poses possible situations, events, or interpretations.

What Vannini proposes is to be reflexive on what we do, being sceptic (why not?) about what we think. Two moods also help with this goal:

- The desiderative mood expresses wishes and desires.

- The volitive mood, which is similarly used to express wish and desire, as well as fear.

These explorations help to defamiliarize our own ideas, our own modes of existence.

Playing with the Sensorium

The architect Barbara Erwine (2016)proposed to play with the senses to create different spaces. Light, somatic, thermal, acoustic or olfactory senses enable new combinations to attune to local atmospheres. Far from the five senses, human and non-human animals present more than one hundred senses. The historian Purnell, explored how do western society arrived to impose some of them over the others for define the perception of our experience.

Playing with the combination of senses is not only choosing to excite one or another, but combine them at different levels, or explore the possibilities to discover unused ones. The benefit is where we can become different, and different atmospheres and spatialities can being reconfigured.

Thinking with care

Puig de la Bellacasa recovers Haraway’s explorations to think about care in terms of: thinking-with, dissenting-within, and thinking-for. Is a ‘a thick, noninnocent requisite of collective thinking in interdependent worlds’ (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 19)

The process of thinking with care is not to reduce it to epistemological positions. Care is a diverse range of doings needed to create, hold together, and sustain life and continue its diverseness. Care is relational, by definition. Thus, thinking with care invites to think ontologically and constantly confront and put into question the boundaries and cuts given in existing worlds. ‘What and how we enter in relations affects positions and relational ecologies [..]creates new patterns out of previous multiplicities, intervening by adding layers of meaning rather than merely deconstructing or conforming to ready- made categories’ (2017, 72).

In sum, thinking with care is ‘to keep us close to the earthy doings that foster the web of life remains active in these effort’ (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 88). It is to think how, the things we do, create and extend worlds beyond our own bodies that require attention, maintenance and work to be sustained.

Drawing things together (DTT) and Infrastructuring

DTT are a set of strategies that were initially designed by Bruno Latour as different forms of representations of the ongoing and becoming of networks. Those strategies include mapping controversies and opening up matters of concern (Telier 2012). DTT calls for a collaborative practices of working around inscriptions, through thinking with ‘eyes and hands’, or the mundane, rather than mental thinking (Latour 2011).

In relation to thinking with care and DTT, alongside with an influence of Actor-Network Theory, infrastructuring is also a process of questioning the worlds that are created and sustained in an open-ended way (Hillgren, Seravalli, and Emilson 2011).

Infrastructuring can be perceived as a processual and ongoing design process. As a part of the Participatory Design discipline, infrastructuring looks for involving participants in many stages of the process, along with conceiving the creation of potentially public objects thought in terms of design-in-use. Even more, infrastructuring is concerned mainly how to address the multiplicity of publics and counter-publics in the design process (le Dantec and DiSalvo 2013).

Due to the historical and discursive components of any system, infrastructuring is also used in design practices as sensitizing devices for making sense of participation, and to legitimize discourses from participants. Infrastructuring’ stance is, therefore, a social action to think beyond information systems and networks (Halkola, Iivari, and Kuure 2015).

These methods help by focusing on the possibilities even before prototype any device or solution. It is to put things together, either visible, tangible, intangible or imaginary in play, in relation. Far from previous, and more abstract strategies, these methods are closed to a tangible design practices without losing the nature of the in-relation.

Research In the Wild

Prototyping is a common practice in design, however, its evaluation is usually performed in closed environments. Research In the Wild (Rogers and Marshall 2017)is an approach from Human-Computer Interaction that looks for going out the lab and test technological devices and prototypes with everyday scenarios. This seems obvious, but attuning with spaces, senses and other bodies, is the equivalent for our stake on performance.

Here, I moved to a more tangible strategy. But, the benefits are broad, since testing ‘in the wild’ not only gives new insight, but also puts concepts under inquiry, particularly in combination with other methods.

Digital Mashups or interactive compositions

Moving towards more pragmatic strategies, we consider the interplay between material possibilities, on what sheller calls vital methodologies. This could also be also inscribed in research-creation, however, I identify it by the importance of digital media.

She calls for challenging the uses of digital tools to provoke, inspire and activate new social practices and performances. Through images, sounds and other forms of mobile media, hybrid spaces can ‘blur the distinction between physical and digital, bodily and virtual, artwork and everyday space, creator and audience’ (Sheller in Vannini 2015, 135). The idea is to enact a provocative awareness of such spaces. ‘Every urban space is in fact infused with layers of moving histories, differently embodied people, and material objects passing through these spaces and leaving traces of their being, of being there’ (Vannini 2015, 140).

This is not different from other practices on design, such as urban informatics or Human-Computer Interaction. However, the intention is more explorative in a non-representational form than creating an effect with a particular goal.

Collect

Because this is an intersubjective approach, collect methods are usually based on ethnographic methodologies, and other forms of registrations.

Ethnographic interviews and thick description

Ethnographic work is nothing new in several disciplines. Even in design research, ethnographic-informed design is common (Dourish and Bell 2011). Geertz’ concept of thick description (Geertz 1973)was foundational for anthropology, where the study of culture is the study of individual and collective practices. Ethnography is just a form of knowledge, based on empirical and interpretative methods. However, using interviews, auto-ethnographies (Lupton 2017)and other forms of speculations (Nova 2015; Nova et al. 2012)are recognized through different disciplines.

Go-alongs

The ‘go-along’ method can be performed by different modes of mobility, one of the most often is walk-alongs. A walk-along is an in-depth qualitative interview method that is useful ‘for exploring and subsequently improving understanding of people’s experiences of their local residential context’ (Carpiano 2009, 3). It facilitates the analysis of everyday practices in place, the relations with other agents, and to keep sensitive to the affective dimension of place-making activities (Duff 2010).

Walking is currently marking a trend within social sciences (Bates and Rhys-Taylor 2017), and it could be also thought as a form of research-creation (Springgay and Truman 2018b). ‘Walking is positioned and understood as a socio-technical assemblage that enables specific attention to be drawn to the embodied, material and technological relations and their significance for engaging with everyday urban movements on foot’ (Middleton 2010).

But focusing on go-alongs, these activities can also be performed in other forms of movements, such biking, running, driving, etc. With the go-along process, it can be understood better the relations between daily practices, participants’ meaning of the places, and the environmental conditions in that those practices take place. Go-Along methods can be useful to record audio and video or take pictures along the activity to be used later as a form of ethnography and attunement with it.

A great example can be found on the Open Source Sound Scapes(Hush City Mobile Lab directed by Dr. Antonella Radicchi) project that use walking and soundscapes for analysing environmental condition.

Mapping workshops

Alongside with infrastructuring and DTT, mapping practices not only work for materializing networks, but also to make sense and recollect memories, experiences and processes. It could be traditional cartographic maps, sketches for navigational purposes, or artifact ecologies. In one of my research experiments, we explored mappings in various forms, that led to discussions about the nature of feelings and the importance of spaces by different means (Portela, Acedo, and Granell-canut 2018).

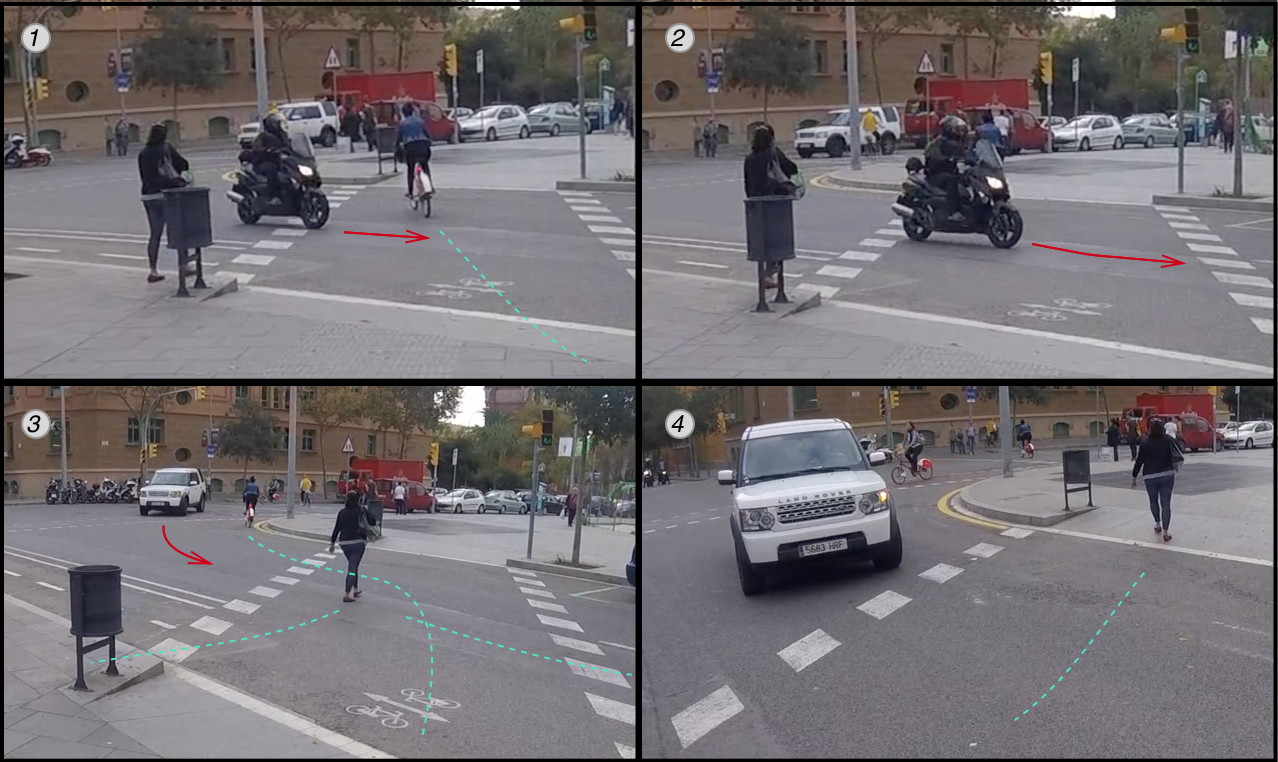

In-situ walkthrough

Walkthroughs(Millen 2000; Kefalidou and Sharples 2016)are used often in HCI and Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) to test devices, interfaces and interactions. However, similar with In the Wild, we can take advantage of following an ethnographic practice and mapping techniques with a subsequent interaction analysis to study how people may use, understand or make sense of the ecologies of practice.

Interaction sketches

Another form of ethnography is what Is doing sketches from direct observation or from video recordings. The useful thing about sketches is the possibility to model specific characteristics of movements and gestures. Sketches are a form of creating during research. Sketching is not only a practice of modeling what is happening, but to recreate through abstraction (Liberman 2014).

These sketches can represent or abstract different time-spaces, groups, senses, activities. Researchers should not reduce their sketching capacities to what is visible, tangible, or even sensed by themselves. Sketches also can be collaborative, as in DTT, as well as made from different materials.

Geographies of Rhythms

I already mentioned the imporance to develop an attentive attitude towards different things, however life is full of rhythms that define forms of existence. Following Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis, Tim Edensor developed the idea of geographies of rhythms (Edensor 2010). We can find rhythms in biological and artificial bodies, that run at different pace, are synchronized or are confronted in discordia. We find rhythms in vibrations and waves, such light and sound. We also find the rhythm of social life, forms of mobilities and forms of communication.

Rhythms also affect the rhythm of others, constitute atmospheres and ecologies; and, also define ecosystems. Being attentive to rhythms can be useful to collect information of others forms of life-creations, other materialities, and diverse forms of relations. Thus, collect such rhythms also are related with the technical forms of record them. From sketches to audiovisual forms of recordings, to other less common artifacts can be useful, where experimentation could open the doors to new forms of unexpected worlds.

Listening to things

One form of rhythm is materialized in the vibrations that are felt by our senses. Sight, is particularly over-explored, we abstract groups and behavior through sight. However, listening is less popular. For that reason, it is a current trend to pay more attention to listen different forms of life. Following the thinking with care perspective, listening involves a sense of being-with that constitutes a communitarian sense, rather than a process of individuation.

Elspeth Probyn (In Vannini 2015)studied how to approach the conflictive representation of environmental issues, in terms of becoming others. This follows the varieties of empathies that Aaltola (2018)tried to develop. How do we feel an ocean? How is to being a fish? And how is the life in the shoal? What can we learn from things that are happening on the ground?

Similarly, Puig de la Bellacasa explored the life of soil. The different kingdoms and their conviviality. The necessity to make it work, altogether in a form of caring.

All these forms of listening not only respond to sound. ‘Investigating the geographies of sound involves following chains of association across a range of spaces and corporealities, working transversally in a motion of propagation like sound itself’ (Gallagher, Kanngieser, and Prior 2016, 620). Instead, listening means to attune to in a form that we ask ‘how do bodies respond to?’

Analyse

Becoming attentive to what happens, or what bodies do, should be considered under the same procedural approach. However, some methods work also in different space-times. In other words, some are useful for analysis during the performance, others work on memory recollection or attunement taking the researcher to feel similar or different things, to re-think and to perceive other virtualities of the same event.

Affective circulation

The notion of Affects appears under a post-phenomenological position, in which embodied experience and practices, including the sensory and sensual, are the focus. Its emergent precarity makes unclear how they behave, and how do we can analyse them.

Thus, first attempts centred on the idea of their emergent circulation and contagion. For example, David Bissell (2010)studied how people is felt in their commuting behavior. Or, Deborah Lupton (2017)studied how affects circulate through health institutions.

However, ‘the biggest difficulty in witnessing how affect enacts space-time is, therefore, the tendency to reduce the movement of capacities to affect and be affected back into a subject-object ontology’. Consequently, there is no a priori assumption here as to the scale effects of their emergence or movement of affect. That results, on that ‘the excessive movement of affect, which we could think through processes such as circulation, flow, transmission or contagion, is an event autonomous of specific determinations’ (2006, 736).

That results on the necessity to difference affects from other modalities. ‘Movements of affect are expressed through those proprioceptive and visceral shifts in the background habits and postures, of a body that are commonly described as “feelings”’.

So, affects, feelings and emotions are different modalities, that don’t act in a linear movement. They don’t present a priori direction or causality in between them. Instead, ‘emotions and feelings are produced through actualizations and can never coincide with the totality of potential affective expression’ (2006, 738). Therefore, affects are considered an excess that is manifested by other modalities.

Atmospheric methods and attunements

Affects can also appear in collective modes. Affective Atmospheres can be understood as the ongoing sensory and affective engagement with our lives and their impressions, sensations and feelings and the environments (Anderson and Ash 2015, 15).

They have effects on and emanate from multiple objects which they relate with, the approach to atmospheric methods is focused on the organisation of physical encounters, ‘where affects emerge when two beings or entities contact one another in some way’ (2015, 35).

Like with affects, the issue about atmospheres is its immanence and the difficulty on grasp their emergence in the liminality. Naming atmospheres will ‘render them subject to intervention’ (2015, 36), beyond the complications appear around the act of generalising and simplifying an atmosphere with denomination. Thus, some affects can be part of atmospheres or constitute more than one, and they can change or transform them. Yet, bodies and objects can be touched while they are out of the atmospheres.

Studying the causes and effects of atmospheres is to be submerged in their ambiguity. So, the authors suggest treating them as affective propositions. Even when atmospheres are irreducible phenomena, they are also an emergent cause since ‘we cannot be sure of the character of the atmosphere before registering its effects in what bodies do’ (2015, 44).

Finally, considering how affects generate changes between bodies and objects, atmospheres have, on one hand, a threshold of internal change that is a consequence of the mass and the configuration of those bodies and objects, and on the other, a tipping point where atmospheres stop emanating and are overridden or subsumedby another atmosphere.

Beyond identifying and studying atmospheric phenomena Sumartojo and Pink (2018)approached different forms of knowing…:

- In atmospheres: the implication is that we need to seek ways to understand what it means to be in and part of the process whereby the atmospheres we inhabit and help to configure are ongoingly emergent. (2018, 36).

- Through atmospheres: the implication is that we need to attend to what thinking atmospherically draws into being or makes it possible to know.

- About atmospheres: means investigating something in the past, even when it might be the quite immediate past (2018, 41).

Noticing, through interaction analysis

‘The answer lies in the desire to put exceptional effort into both recording and then noticing (in the recording) those very practices that produce the unexceptional looks of things. […] What a visual analysis would mean here, therefore, is addressing the visual analysis of these members of the set- ting that we are studying. Their visual analysis is what we will then attempt to describe’ (Laurier 2014, 256).

The exercise consists in using different forms of analysis of recordings, to defamiliarize with it and notice different things. Noticing gestures, movements, and objects allows the analyst to re-specify those earlier problems and impasses that are practical for the locals. Thus, ‘we can notice things in video recordings of collective practices that ask us to change our minds about what things mean and how they mean to the groups that we study’ (2014, 272).

Noticing also can be convenient using also non-audiovisual material. Using conversational analysis in a classic way — through transcriptions (Sacks 1992; Jefferson 2004), meaning can pop-up from studying language construction and communication gestures.

Shared analysis

Studying experiences can be also analysed backwards. Like in knowing about atmospheres, a shared analysis includes ‘an encounter between the researcher and research participant, and/or materials that have been made about the past. Such materials constitute “participants” traces through the world as a shareable experience and [create] new ways of understanding it’ (Sumartojo and Pink 2018, 44).

If not things from the past, also simulations and models can be used for doing shared analysis. That is the case analysed in (Rose, Degen, and Melhuish 2014; Degen, Melhuish, and Rose 2017) where architectural modelling implies the reproduction of an experience.

Other shared analysis can be performed in doing interaction analysis or ethnomethodology, like in the example that I’ve shared previously where meaning is discussed in-between.

Structures of feelings (SoF)

A structure of feeling is a collective dispositional relation to the world, that conditions how something appears by organising the way in which it comes to be felt as part of the dynamics of everyday life.

‘Structures of feeling effect in a twofold sense in that they both ‘pressure’ and ‘limit’ our relation to ourselves, others and the world. They exist as both dispositional attunements and affective qualities. There is also strangeness to the idea: structures of feeling are emergent and revealed through their traces. They can never be fully summed up and accounted for’ (Anderson 2014, 124).

SoF are emergent, precarious, vague, and uncertain. It is also ambivalent: ‘a site of pain and hope, loss and possibility’ (2014, 129). SoF may also come to coexist with one another. Additionally, ‘a single structure of feeling cannot be reduced to an apparatus. […] Apparatuses are not necessarily contemporaneous with structures of feeling’ (2014, 133).

SoF are sensed or felt in encounters, are lived. Therefore, ‘structures of feeling act as affective conditions in the specific sense that they “bestow an enigmatic coherence” and predispose relations to self, others, and the world’ (2014, 135).

Modes of Orderings

Modes of ordering are presented as a non-reductionist method and a set of ‘specific strategies of reflexivity and self-reflexivity’ (Law 1994, 107). Modes of Ordering looks for patterns that ‘embody, generate, or perform agent-relevant economies of scale. Thus, agents do not have to deal with all the intricacies of the networks that they confront and seek to translate.’ (1994, 108).

One clear example of how to study modes of orderings is in the work of Moser(2005; 2006), who analyses disability in public places. On Moser’s own words, ‘disability is not something a person is, but something a person becomes. The question is how people become and are made, disabled and what the possibilities for articulating alternatives are’ (Moser 2005, 668). This results on that disability is socially shaped. Also, disability does not depend only on the ability to move around, also depends on how apparatuses of discourse create, materialise and normalise this condition. People do not live in just one coherently arranged mode of ordering, but multiple and varied. The process of ordering is emergent, precarious and recursive. What can be useful is to understand how thepublics emerge in different material relations, and what orders are enacted on them.

These modes of ordering can be found in interaction with objects, digital artifacts and other bodies (Moser 2006). The ability to understand and manage our action is not only cognitive and logical, but also social. Consequently, modes of orderings are other form of being attentive to what happens, but seek for the effects of social relations.

How to deal with methods

The benefit on using diverse approaches is not only the possibility to explore different assemblages, but to reconfigure our own knowledge and the assumptions that carry our methodological approach.

By exploring combinations of the various methods, designers and researchers can break down individual and social assumptions and explore ways to enact new forms of becoming together and affective translations. The importance is always to thinking-doing, rather to follow a linear path.

During my research, I’ve used these strategies to set up experiments, to analyse results, but also as inspirational tools. Thanks to them, I’ve also re-purposed material from one experiment to thinking-doing from different standpoints. For example, in one of my published experiments (Portela, Acedo, and Granell-canut 2018), I’ve worked with spaces and places under different perspectives, using maps for different purposes, setting go-alongs to defamiliarize and used noticing and video analysis to attune to the past experience.

To what refers to UX Research, new insights can be found when we look beyond ‘use’ and ‘intention’. In my experience with chatbots, cross-domain strategies helped me to define better the individual and social implications of novel platforms (Portela and Granell-canut 2017). Some other pragmatic examples can be found in projects like Who wants to be a self driving car, WereAQ or Voiceover.

I want invite readers to explore the references, and to experiment with these methods to expand personal assumptions and become sceptic for creative purposes.

‘Methods are multi-farious and contagious, and exist throughout the duration of a research event propelling thinking-making-doing forward into the next speculative middle’ (Springgay and Truman 2018a, 10).

References

Aaltola, Elisa. 2018. Varieties of Empathy: Moral Psychology and Animal Ethics. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Anderson, Ben. 2006. “Becoming and Being Hopeful: Towards a Theory of Affect.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space24 (5): 733–52. doi:10.1068/d393t.

— — — . 2014. Encountering Affect: Capacities, Apparatuses, Conditions. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14649365.2015.1078146.

Anderson, Ben, and James Ash. 2015. “Atmospheric Methods.” Nonrepresentational Methods: Re-Envisioning Research, 34–51. http://www.academia.edu/10294576/Atmospheric_Methods.

Bates, Charlotte, and Alex Rhys-Taylor. 2017. Walking through Social Research. Walking Through Social Research. doi:10.4324/9781315561547.

Bissell, David. 2010. “Passenger Mobilities: Affective Atmospheres and the Sociality of Public Transport.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space28 (2): 270–89. doi:10.1068/d3909.

Carpiano, Richard M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with Me: The ‘Go-Along’ Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health and Place15 (1): 263–72. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

Dantec, Christopher A. le, and Carl DiSalvo. 2013. “Infrastructuring and the Formation of Publics in Participatory Design.” Social Studies of Science43 (2): 241–64. doi:10.1177/0306312712471581.

Degen, Monica, Clare Melhuish, and Gillian Rose. 2017. “Producing Place Atmospheres Digitally: Architecture, Digital Visualisation Practices and the Experience Economy.” Journal of Consumer Culture17 (1): 1–25.

Dourish, Paul, and Genevieve Bell. 2011. Divining a Digital Future: Mess and Mythology in Ubiquitous Computing. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Duff, Cameron. 2010. “On the Role of Affect and Practice in the Production of Place.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space28 (5): 881–95. doi:10.1068/d16209.

Edensor, Tim, ed. 2010. Geographies of Rhythm: Nature, Place, Mobilities and Bodies. Manchester: Ashgate.

Erwine, B. 2016. Creating Sensory Spaces: The Architecture of the Invisible. London: Routledge. https://books.google.es/books?id=Si4lDwAAQBAJ.

Gallagher, Michael, Anja Kanngieser, and Jonathan Prior. 2016. “Listening Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography41 (5): 030913251665295. doi:10.1177/0309132516652952.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays.New York: Basic Books.

Halkola, Eija, Netta Iivari, and Leena Kuure. 2015. “Infrastructuring as Social Action.” Icis, 1–19.

Hillgren, Per Anders, Anna Seravalli, and Anders Emilson. 2011. “Prototyping and Infrastructuring in Design for Social Innovation.” CoDesign7 (3–4): 169–83. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.630474.

Jefferson, Gail. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversational Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by Gene H. Lerner, 13–31. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Kefalidou, Genovefa, and Sarah Sharples. 2016. “Encouraging Serendipity in Research: Designing Technologies to Support Connection-Making.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies89 (May). Elsevier: 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.01.003.

Latour, Bruno. 2008. “A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (with Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk).” Design History Society, 2.

— — — . 2011. “Drawing Things Together.”The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation. Wiley Online Library, 65–72.

Laurier, Eric. 2014. “Noticing.” In The SAGE Handbook of Human Geography, 254–76. SAGE Publications.

Law, John. 1994. Organizing Modernity: Social Ordering and Social Theory. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing.

Liberman, Kenneth. 2014. “Following Sketched Maps.” In More Studies in Ethnomethodology, 45–82. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lupton, Deborah. 2017. “How Does Health Feel? Towards Research on the Affective Atmospheres of Digital Health.” Digital Health3: 205520761770127. doi:10.1177/2055207617701276.

Marres, Noortje, Michael Guggenheim, and Alex Wilkie. 2018. Inventing the Social. Vol. 37.

Middleton, Jennie. 2010. “Sense and the City: Exploring the Embodied Geographies of Urban Walking.” Social & Cultural Geography11 (6): 575–96. doi:10.1080/14649365.2010.497913.

Millen, David R. 2000. “Rapid Ethnography: Time Deepening Strategies for HCI Field Research.” Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods and Techniques, 280–88. doi:10.1145/347642.347763.

Moser, Ingunn. 2005. “On Becoming Disabled and Articulating Alternatives.” Cultural Studies19 (6): 667–700. doi:10.1080/09502380500365648.

— — — . 2006. “Disability and the Promises of Technology: Technology, Subjectivity and Embodiment within an Order of the Normal.” Information, Communication & Society9 (3): 373–95. doi:10.1080/13691180600751348.

Nova, Nicolas. 2015. “Design Ethnography? Towards a Designerly Approach to Field Research.” In Empowering Users through Design Interdisciplinary Studies and Combined Approaches for Technological Products and Services, edited by D. Bihanic, 119–28. Switzerland: Springer.

Nova, Nicolas, Katherine Miyake, Walton Chiu, and Kown Nancy. 2012. Curious Rituals: Gestural Interaction in the Digital Everyday. Near Future Laboratory.

Portela, Manuel, Albert Acedo, and Carlos Granell-canut. 2018. “Looking for ‘ in-between ’ Places.” Media Theory Journal2 (1): 108–33. http://mediatheoryjournal.org/portela-et-al-looking-for-in-between-places/.

Portela, Manuel, and Carlos Granell-canut. 2017. “A New Friend in Our Smartphone ? Observing Interactions with Chatbots in the Search of Emotional Engagement.” In Proceedings of Interacción ’17. doi:10.1145/3123818.3123826.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. doi:10.15713/ins.mmj.3.

Rogers, Yvonne, and Paul Marshall. 2017. “Research in the Wild.” Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics10 (3). Morgan & Claypool Publishers: i — 97.

Rose, Gillian, Monica Degen, and Clare Melhuish. 2014. “Networks, Interfaces, and Computer-Generated Images: Learning from Digital Visualisations of Urban Redevelopment Projects.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space32 (3): 386–403. doi:10.1068/d13113p.

Sacks, Harvey. 1992. Lectures on Conversation. Victoria. Vol. 1. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444328301.

Springgay, Stephanie, and Sarah E. Truman. 2018a. “On the Need for Methods Beyond Proceduralism: Speculative Middles, (In)Tensions, and Response-Ability in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry24 (3): 203–14. doi:10.1177/1077800417704464.

Springgay, Stephanie, and Sarah E Truman. 2018b. Walking Methodologies in a More-than-Human World: WalkingLAb. London: Routledge.

Storni, Cristiano. 2016. “Notes on ANT for Designers : Ontological , Methodological and Epistemological Turn in Collaborative Design.” International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts0882 (February). doi:10.1080/15710882.2015.1081242.

Sumartojo, S, and S Pink. 2018. Atmospheres and the Experiential World: Theory and Methods. Ambiances, Atmospheres and Sensory Experiences of Spaces. Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.es/books?id=KiBtDwAAQBAJ.

Telier, A. 2012. “Drawing Things Together.” Interactions19 (2): 34. doi:10.1145/2090150.2090160.

Vannini, Phillip. 2015. Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. London: Routledge.